|

|

|

|

|

|

SUPERIOR FORCE

: The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of

Goeben and Breslau

© Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 3

|

|

The First Shot

|

|

|

HMS Indefatigable

photographed later during the War |

Following

the junction of Goeben and

Breslau

at Messina on 2 August, Souchon’s immediate thoughts turned to coaling. Not

only was this filthy job hated by all on board but, with

Goeben’s

high consumption, it was a time-consuming operation made worse by the absence of

dependable sources of supply. Souchon was credited by his enemies with having

colliers scattered along the route of his most likely destination – the western

basin of the Mediterranean – and, indeed, one of these “phantom” ships would add

to the confusion of both the British and French. |

|

The reality was

far more prosaic and depended, for the most part, on hasty improvisation.

Souchon had remembered that the German East African Line steamer

General, bound for an exhibition at Dar-es-Salaam, was in the

vicinity: he recalled it from Crete, ordered it to Messina, and requisitioned it

as a supply ship. His foresight was justified as choppy seas at Brindisi had

provided the Italians with enough of an excuse to deny Souchon coaling

facilities; he must have realized that his reception at Messina was unlikely to

prove any more welcoming.[1]

Pressure had been growing meanwhile

for the two ships to be sent to Constantinople. Secret negotiations being

conducted there with a view to concluding a Turco-German alliance were well

advanced by 1 August when the Austrian Ambassador reported to the tremulous

Grand Vizier that the latest reliable information received from Vienna pointed

to an attack on the Bosphorus by the Russian Black Sea Fleet. As unlikely as

this was, the German Ambassador, Baron von Wangenheim, saw his chance and cabled

to his Foreign Office that if Goeben could be spared she could, by reinforcing the Turkish fleet,

hold off the Russians. This would have the effect both of assuring the cable

connection with Roumania and preventing a Russian landing on the Bulgarian coast

— and, Wangenheim need hardly have added, would have done no harm to the

alliance negotiations. The Ambassador was to be disappointed however: at 9.15

p.m. on the evening of Sunday 2 August the Kaiser replied, through his

aide-de-camp, that Goeben could not be

dispensed with at the present time. Admiral von Pohl, the Chief of the German

Admiralty Staff, not only agreed but maintained that Goeben

could provide the greatest service in the Atlantic or North Sea and had no

business in Turkish waters. Unknown to either Wilhelm or von Pohl – as

knowledge of this would not be received in Berlin until the following morning

– the Turco-German treaty of alliance had already been signed that Sunday at 4

p.m.[2]

The situation then late on the

afternoon of Sunday 2nd was that, although the Cabinet in London was still

agonizing, intervention in the war now seemed the most likely course; in Paris

uproar and confusion reigned following the breakdown of the Minister of Marine;

the German Ambassador in Constantinople had the text of the Turco-German

alliance in his pocket; at Malta, Milne had briefed Troubridge who had in turn

briefed his captains and would shortly sail; at Toulon, Lapeyrère prevaricated;

and Souchon coaled as best he could in Messina from steamers in the harbour. The

news Souchon received from Berlin was not good: hostilities had commenced

against Russia, war with France was certain and would probably begin on the 3rd,

Great Britain would ‘very probably’ be hostile and Italy neutral.[3]

No mention was made of the attitude of Austria-Hungary and no specific orders

were given to Souchon; he therefore took matters into his own hands and drew up

a plan to bombard the ports of Philippeville and Bona on the Algerian coast in

an attempt to disrupt the passage of the French XIXth Army Corps.

After taking in a small amount of

coal of varying quality Souchon was able to slip quietly out of port under cover

of darkness at 1 a.m. on the night of 2/3 August, his two ships heading west at

17 knots. As the ships cleaved their way through the shimmering water during the

following day (Monday 3rd) Souchon framed his intentions: to harass and delay

the transportation so that the French would have ‘to make great efforts to

protect them.’ To accomplish this, at daybreak the next morning, Tuesday,

Goeben

would be off Philippeville and Breslau

off Bona where they would hoist Russian colours, so as to be able to approach

the shore without raising an alarm, and ascertain what ships were lying in the

harbours. Then German colours would be broken out and the ports and ships

bombarded by gunfire (or torpedoes if necessary); ammunition was to be used

sparingly, while a gun duel between the ships and the shore batteries was to be

avoided. Afterwards the two ships would continue to steer to the west until out

of sight of land before turning to rendezvous near Cape Spartivento on the

southern edge of Sardinia.[4]

Although Souchon’s intentions thereafter were not stated his options were

limited, and a breakout into the Atlantic does not appear to have figured

amongst them; perhaps he just wanted to play for time, to see what Admiral Haus

and the Austrian fleet would do. Ultimately, the continued necessity to obtain

coal would impose its own limitations upon Souchon’s movements, but not

without some belated direction from Berlin.

Having become aware, late on the

morning of Monday 3rd, of the signing of the alliance in Constantinople Admiral

von Pohl in Berlin began to relent in his earlier opposition to

Goeben

going east, his reluctance finally being overcome by the enthusiasm of Tirpitz.[5]

Within hours – and upon their own authority – Pohl and Tirpitz issued orders

for Goeben and

Breslau

to proceed to Constantinople. Wilhelm, having subsequently been informed, agreed

and the Foreign Office duly sent a cable to Ambassador Wangenheim at 7.30 that

evening to notify him of the change in plans and suggest that Souchon should be

placed at the disposal of the Turks to command their fleet.[6]

Souchon had already learned on the evening of the 3rd, just before his two ships

parted company on their respective missions, that war had broken out with

France. This message, transmitted via the W/T station at Vittoria on Sicily, was

delayed as both Duke of Edinburgh and

Defence

attempted to jam the signal; the German signal was also intercepted aboard

Indomitable

at 5.7 p.m. but all they could make out was what they assumed to be the end of

the message, which was, confusingly, in French: ‘I will give you more later

keep a good watch.’[7]

A few hours afterwards the message

was flashed from the W/T station at Nauen that an alliance had been concluded

with Turkey and that the two ships were to proceed immediately to

Constantinople. The signal was intercepted by receiving stations in England and

telegraphed to London at 2.4 a.m. but it would not be until November that the

German codes could be read.[8]

Souchon received the unexpected message some two hours before his ships were due

to open fire on the French North African ports. ‘To turn round immediately,’

he later wrote, ‘on the verge of the eagerly anticipated action, was more than

I could bring my-self to do.’[9]

Instead he held to his course and to his intention. Arriving off Philippeville

at dawn, Goeben had to slow as two

suspicious steamers passed out of the harbour and it was only at 6.8 a.m. that

her guns un-leashed a short, violent bombardment. Ten minutes later she was in

flight on a westerly course, pursued in-effectively by a few shells lobbed by a

French howitzer battery. Breslau had

an even easier time of it, making her run past Bona with guns blazing and no

reply. The opening shots in the Mediterranean had been fired.[10]

No previous account of this

bombardment has mentioned the fact that, the following day, a report was

received in London from the consul at Algiers stating that, during the shelling,

the British ship Isle of Hastings had

been seriously damaged. It would be interesting to speculate what effect this

news might have had on the deliberations in London on 4 August if it had arrived

immediately by acting as a casus belli to justify forthwith the instigation of hostilities in

the Mediterranean. There seems little doubt that Churchill would have put this

information to good use if available in time but, with the delay in reporting

and the pressure on the wires, it was not received at the Foreign Office until

just after midday on the 5th.[11]

The Germans had been just as anxious as the British and French to avoid

committing the first act of aggression — at 8.50 on Monday evening (3 August)

the German Admiralty Staff had telephoned the Fleet Commander to warn him ‘to

avoid all movements or actions that might be construed by England as directed

against herself. Auxiliary cruisers not to be allowed to run out, therefore.’[12]

Souchon, as unaware of this directive as the Admiralty Staff were of his own

intentions, had violated and undermined the carefully preserved position adopted

by Berlin.

The

news that Goeben and

Breslau

had arrived at Messina shortly after midday on Sunday 2nd became known to Milne

later that night: at 2.59 a.m. he relayed the message to Troubridge’s squadron

and also to Chatham, which had been

detailed in any event to search Messina. In an instant display of the confusion

attendant upon his dual objectives Troubridge wanted to know whether he should

continue to watch the Adriatic. Milne’s reply, passing on Churchill’s order,

was not particularly helpful: ‘Yes, but Goeben

is primary consideration…’ Milne also ordered

Chatham to go right through the Straits of Messina so that she might

be able to report if Souchon had gone north.[13]

Having digested Milne’s orders but with no accurate knowledge as to the

present whereabouts of the German ships, which may or may not have been still in

Messina, Troubridge signalled back at 5.6 a.m. asking if he should send the two

battle cruisers to the west by way of the southern route round Sicily. Milne

considered this action premature until authentic news had been received.[14]

Therefore, until Chatham could report,

Troubridge took up a position south-east of the Straits of Messina where he

could reasonably hope to intercept any ships coming south; if, on the other

hand, Goeben and

Breslau

proceeded north out of the Straits, he intended to act, as already indicated, by

sending Indomitable and

Indefatigable round the south of Sicily as he would not risk sending

the battle cruisers through the narrow Straits in view of the uncertain attitude

of Italy.[15]

Chatham,

however, was expendable and the light cruiser passed through the Straits at 7.30

that morning (3 August); she had missed Goeben

and Breslau by a little over six

hours.[16]

Milne directed the cruiser to head west once out of the Straits, round the

northern coast of Sicily, and endeavour to find Goeben, if necessary by asking passing merchant ships for

information.[17]

He also informed the Admiralty that Troubridge’s force would now reverse

course and search to the west, ‘towards French transport line from Algiers’,

with the exception of the light cruiser Gloucester and eight destroyers which were detached to maintain a

tenuous watch on the Adriatic. The decision to order Troubridge to search to the

west apparently resulted after Milne had received intelligence that

Goeben

and Breslau had been sighted off the coast of Calabria the previous day

steering south-west.[18]

As they were no longer in Messina Milne could not be certain that the German

ships had slipped through the Malta Channel to the south of Sicily, in which

case they would run into Troubridge who was now blocking this passage. Milne’s

message detailing these dispositions was received in London at 9.05 a.m. on the

3rd, to the apparent satisfaction of Sturdee, the C.O.S., who pencilled a note

for the benefit of the French Naval Attaché, ‘C-in-C is evidently doing all

he can.’[19]

The problem of the French troop transports would continue to cause anxiety until

the afternoon of the following day when news was first received in London that

the sailings had been postponed on Lapeyrère’s orders due to the uncertainty

as to the whereabouts of Goeben and

Breslau.

Souchon’s calculated decision to ignore his new orders from Berlin – at

least until he had completed his planned bombardments – thus brought an

immediate bonus.

Out at sea, Troubridge and most of

his squadron were now steaming back in the direction of Malta. Captain Kennedy

aboard Indomitable could see no

obvious reason for the about face unless it could be that the Italians had

entered the war and, as he had not been as convinced as some that they would

remain neutral, he semaphored quizzically to Defence, ‘Where is “Taranto Fleet”? Between us and Malta?’

Troubridge did not know to what fleet Kennedy was referring and asked for more

information, which Kennedy could not supply. Nevertheless, the Captain of

Indomitable

did not want to be caught napping and, as he was senior to Captain Sowerby in

the other battle cruiser, Indefatigable,

he signalled the latter at 10.10 a.m., ‘If we are detached and coming into

action with enemy I hope you will haul out of “line ahead” if we are in that

formation, sufficiently to use your guns without signal from me (stop) and to

save coal keep just out of our wake as a rule only getting into it when we are

turning…’[20]

As Kennedy prepared for the

possibility of action with the Italians Milne was already having second

thoughts. Worried that he had not left the entrance to the Adriatic sufficiently

covered by Gloucester and the

destroyers, Milne now ordered Troubridge to alter course again and send the

First Cruiser Squadron back to assist

in watching the Adriatic while the two battle cruisers alone were to be detached

to continue their westward passage.[21]

Defence duly logged this signal and,

at 3.15 on the afternoon of Monday, 3 August, Troubridge detached

Indomitable

and Indefatigable from his flag[22]

as he himself turned his heavy cruisers about and returned to the patrol line at

the entrance of the Adriatic. Two hours later, when 20 miles off Valletta,

Captain Kennedy was ordered to proceed at 14 knots to search for

Goeben

and Breslau between Cape Bon and Cape Spartivento; the two British

battle cruisers were instructed not to separate too far and to be on their guard

against surprise attack; fires were to be lighted in all boilers.[23]

At this time Chatham (having passed

through the Straits of Messina) was off the north-west tip of Sicily, proceeding

on her circumnavigation of the island, after having discovered no further

information about the Germans who, at the time, were further still to the west

on their way to Philippeville and Bona.

In London on the 3rd Battenberg too

had little information to go on: every sighting of Souchon had placed him

further west. France and Germany were then not yet at war, though it would only

be a matter of hours, however Prince Louis did not even know if the French fleet

had sailed or not. With no clear idea as to the intentions of the French,

Battenberg must have reasoned that Souchon was apparently either trying to

interfere with the French transports or else escape into the Atlantic, or

possibly both. That afternoon the Senior Naval Officer, Gibraltar was therefore

warned that, as Goeben and

Breslau

had ‘got away from the British battle cruisers’, a patrol should be formed

to watch the Straits of Gibraltar. Having thus planted the suspicion in his own

mind the seed germinated and took root and, at 6.30 p.m., Battenberg drafted new

orders to Milne: ‘The two battle-cruisers must proceed to Straits of Gibraltar

at high speed ready to prevent Goeben

leaving Mediterranean.’[24]

Milne received the signal at 8.30 p.m. and it was flashed immediately to Captain

Kennedy, who was handed it on his bridge 17 minutes later — steam was raised

for 22 knots, close to the maximum speed of the battle cruisers in their current

state, forcing Kennedy to use oil in addition to coal, as required. As the

battle cruisers increased speed, the Foreign Office received a report from the

Naval Attaché in Paris that the French fleet had sailed that morning ‘to

watch German cruiser Goeben and protect transport of French African troops, which will

commence tomorrow.’ Although Sturdee initialled the Admiralty copy, the

information was not relayed to Milne who had finally left Malta at 6.30 that

evening in Inflexible and now lay

stopped in the Malta Channel ‘so as to be ready for immediate action if

necessary.’[25]

This new information from Paris had, to a certain extent, made redundant

Battenberg’s order less than two hours previously regarding the battle

cruisers yet no further action was taken, leaving Indomitable and

Indefatigable

to continue that night on their new westward course.

The situation in the still, moonlit

sea as Monday 3 August passed quietly into Tuesday 4th was thus:

Goeben

and Breslau, aware now of the outbreak

of war between Germany and France, had separated and were racing to the Algerian

coast to pursue their respective missions of destruction; Milne, having been

unsuccessful in his attempts to establish contact with the French, had first

detached two of his three battle cruisers to search westward while he remained

near Malta in the third, then, following Admiralty orders, he had dispatched

them with all haste to Gibraltar; the French fleet, having left Toulon early in

the morning of the 3rd, continued their unhurried, stately progress towards

Africa. The warships of three nations were con-verging in the rectangle of sea

bounded by Majorca, Sardinia and the African coast from Algiers to Bizerta.

In London, at 9.45 p.m. on the 3rd

(following the outbreak of war between France and Germany), Saint-Seine met

Battenberg at the Admiralty where it was decided that the Anglo-French agreement

should be implemented as soon as possible and that it was ‘to be clearly

understood that this implies no offensive action on the part of the British

forces, who will not carry out any warlike action unless attacked by German

forces.’[26]

This meeting had occurred as a result of an approach by Churchill to Asquith and

Grey earlier that day: ‘I must request authorisation immediately’, Churchill

demanded in a tone that left the august recipients in little doubt as to the

answer required, ‘to put into force the combined Anglo-French dispositions for

the defence of the channel. The French have already taken station & this

partial disposition does not ensure security.’ To be absolutely sure, the

First Lord added that ‘My naval colleagues & advisers desire me to press

for this; & unless I am forbidden I shall act accordingly.’ Churchill did,

however, add that this ‘implies no offensive action unless we are attacked.’

The Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary gave their approval at 5 p.m.[27]

Vice-Admiral

Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère had divided his fleet at Toulon into three groups

and, early on the morning of 3 August, having already sent the old ships of the

Reserve Squadron on ahead, the main body departed to rendezvous with them near

the Balearics where the combined force would again separate: the first group, to

the east, under Vice-Admiral Chocheprat, comprised the First Battle Squadron of

six semi-dreadnoughts of the Danton

class, the first division of the Armoured Cruiser Squadron and a flotilla of

destroyers; its destination was Philippeville. The second group, in the centre,

under Lapeyrère in the new dreadnought Courbet,

comprised in addition the pre-dreadnoughts of the Second Battle Squadron, the

second division of the Armoured Cruiser Squadron and 12 destroyers; its

destination was Algiers. The third group, the Reserve Squadron, to the west,

would go to Oran.[28]

The long delayed message from Paris informing the C-in-C of the outbreak of war

was not received on the flagship till just after one o’clock on the morning of

the 4th; this message reiterated, in no uncertain terms, the express wish that

the transports should proceed individually, each at its best speed.[29]

Lapeyrère’s three groups steamed slowly on at an economical cruising speed on

their diverging courses until the startling news of the bombardments was

received: that first Bona, then Philippeville, had been shelled by ships which

raced off in a north-westerly direction, apparently towards the Balearics.

Souchon’s feint had succeeded, helped by the fact that the French believed

that the Germans had a collier stationed in the Balearics from which Souchon

could then base himself to launch further attacks; there was also the immediate

possibility that Souchon would resume a westerly course and bombard Algiers. To

guard against the latter at least Lapeyrère ordered Cocheprat’s first group

to alter course to the south-west, away from Philippeville, and head for Algiers

also. Neither surmise was correct: as soon as he thought he had steamed out of

sight of the coast, Souchon doubled back eastwards, towards Messina.

The first opportunity to intercept

Souchon – which fell to the French – had been lost, but how great had it

been? Although Cocheprat’s destination had originally been Philippeville he

was still well short when the order was given to change course away. Although

the Germans reported that, by their wireless traffic, parts of the French fleet

were ‘in the immediate vicinity’[30]

this was not the first time, nor would it be the last, that wireless operators

reported enemy ships just over the horizon when, in fact, they were scores of

miles away. One mystery concerns Troubridge’s report of a conversation he

subsequently had with Lapeyrère at Malta on 16 August. Troubridge at first

recounted that Lapeyrère ‘had actually sighted Goeben

with his flagship with the First Division of the French Fleet. He was only an

hour and a half behind her himself and actually saw her smoke on the horizon.’[31]

Troubridge later expanded on this: Lapeyrère ‘in the

Courbet

with some battleships in company, had sighted the Goeben’s

masts and smoke at a distance of 25 to 30 miles from him on the morning of the

4th August.’[32]

Both statements are palpable nonsense: Courbet was not with the First Division of the Fleet that morning,

but in the second, central, division heading for Algiers. It was absolutely

impossible for Lapeyrère to have sighted Goeben.

He might have seen smoke on the horizon but in all probability it was from the

ships of his own first division which were now steaming on a converging course

and, at the time, would have been about 30 miles distant. As Lapeyrère spoke no

English Troubridge was possibly misinformed, but as Troubridge also apparently

recalled that the French Admiral ‘at once decided it was futile to endeavour

to close [Goeben]’[33]

perhaps the most charitable explanation is that Lapeyrère, knowing that

Troubridge had aborted his own attempt to intercept the Germans, was simply

consoling the Englishman along the lines of “in your place, I would have done

the same”.[34]

Having left Toulon as late as they

did the French had undeniably robbed themselves of the chance of being off the

African coast at first light on the morning of the 4th; if Lapeyrère had sailed

on the 2nd, which he could have done, could he have brought Souchon to action?

The answer must be a highly qualified “yes”. The division that

Goeben

might have encountered at Philippeville – the first group – comprised as its

main striking force six semi-dreadnoughts, not one capable of exceeding 20

knots; the battle cruiser as a class did not exist in the French navy. Although

Goeben’s

trial speed had been reduced due to her boiler problems she was still capable of

22 knots and, if pushed, up to 24 knots. If Souchon had emerged from the shadows

off Philippeville and blundered into Cocheprat’s group there is little doubt

that he could have escaped east at high speed, a belief supported by the

conclusion of the French Commission appointed to investigate the débâcle:

By

reason of the difference in speed and artillery existing between the ships

making up the French Fleet and the Goeben

and Breslau it is impossible to affirm that if offensive measures had

been taken from the first day of operations the enemy cruisers would have been

captured or destroyed.[35]

This

highlighted one crucial fact: if Souchon were to be caught, it would not be upon

the open sea but as a result of (1) being cut off by a stronger force (without

defining, at this stage, what that might be), or, (2) by being surprised when

immobilized either while coaling or as the result of battle damage inflicted

after (1). Milne’s battle cruisers had all exceeded 26 knots on their trials

but were now capable of no better than 22 knots. Souchon, though he might not

have realized it given the state of his boilers, possessed the priceless

advantage of speed.

News

of the German bombardment reached Milne unofficially, via the Eastern Telegraph

Company, at 8.50 on the morning of the 4th, though this initial report stated

that only Bona had been shelled and that this had been done ‘by three of four

German ships’.[36]

In the confusion however, Milne appeared to think the message referred to Bona

or

Oran being bombarded; by the time he passed the information on to Troubridge

at 10.15 a.m. he mentioned only that Oran had been bombed, and by three German

ships.[37]

It is impossible to ascertain how this error was made but the significance of

the mistake was that, as Oran is closer to Gibraltar than Bona, it tended to

heighten the impression that Goeben

and Breslau would continue to escape

westwards and thereby pointed to the Atlantic as the most probable destination.

Aboard the British battle cruisers, Captains Kennedy and Sowerby passed the time

from 8.30 a.m., as they edged ever closer to Gibraltar, by swapping signals.

Indefatigable

had just semaphored, ‘What do you imagine the situation is at present?’ to

which Indomitable replied that it was

thought England and Italy were still neutral. Kennedy also pointed out that his

ship had been using oil since 9 o’clock the previous night to be able to

maintain 22 knots and that the stokers were to be put into three watches instead

of two but, to accomplish this, 90 ratings would have to be put to work trimming

the bunkers; Kennedy then speculated as to how far west

Goeben might have been able to steam. As if a teasing spirit now

sought to provide an answer, within minutes the intercepted message from the

Eastern Telegraph Company office at Bona was handed to Kennedy on the bridge.

The Captain was dumbfounded: due to an error in coding, the message received by

him stated that the Germans were shelling Dover. Regaining his composure, he

signalled Sowerby at 10.12 a.m., ‘…I do not believe that yarn about Germans

firing on Dover do you?’

Unlike his own, the staff on

Indefatigable

had been doing their homework and had already calculated that, if

Goeben left Messina about midnight on 2/3 August at 14 knots, she

could have been off Bona by 5 a.m.

that morning; it was just possible, they conceded, that

Goeben could make for home round the north of Scotland at 14 knots,

without coaling, though the more logical assumption was for her to put into a

neutral port to obtain further supplies of coal. Kennedy agreed that, especially

if she had taken in a deck cargo of coal, Goeben could ‘get right round North About Home’ without

recoaling, but the idea of shelling Dover on the journey ‘would be a risky and

expensive way to declare war. I think BONA was meant not DOVER.’ Twenty

minutes later, all doubt was removed when the battle cruisers intercepted a W/T

sent to Milne from Dublin which was

then moored in Bizerta harbour on her mission to establish contact with the

French; the message stated that Goeben

and Breslau had fired shots into

Philippeville and Bona and left ‘Full Speed Westward’.[38]

It was Dublin which then proceeded to

cloud the issue by reporting news received from Paris that a German collier was

anchored at Palma, ‘Supposed idea coal 2 German cruisers.’[39]

Milne was snatching snippets of

information out of the ether – that the German ships had bombarded Bona or

possibly Oran and headed off in a westerly direction, and that there was a

German collier in the Balearics – all of which directed his attention to the

western basin of the Mediterranean. At 9.46 that morning the Senior Naval

Officer, Gibraltar reported to London that a message had been received from

Marseilles that German men-of-war had passed along the Algerian coast during the

night, shelling Bona, and were ‘now on the way to Gibraltar.’[40]

It is possible that this message was also intercepted and passed to Milne.

However, with the attendant irony which is never far removed from such

occasions, the most dramatic message that morning – which might have diverted

his gaze away from the west – was not initially received by Milne. At 10.32

a.m. the lookouts aboard Indomitable

spotted Breslau two points off the

starboard bow, proceeding north-east by

east at high speed and throwing up a huge bow wave.[41]

Almost before Captain Kennedy could order ‘Look out for

Goeben’

the German battle cruiser appeared out of the haze off

Indomitable’s

port bow. As action stations sounded it seemed that, to rejoin her consort,

Goeben

was attempting to cut across the bows of Indomitable;

Kennedy thereupon altered course to starboard to block the manoeuvre forcing

Goeben

to resume her original course so that the two battle cruisers, whose countries

still remained at peace, passed each other on opposite courses, travelling at a

combined speed of close to 40 knots.

Kennedy ordered his ship’s guns

kept trained to their securing positions while Goeben

was scanned carefully to see if she flew an admiral’s flag which would require

a salute. In the circumstances, with war perhaps hours away, Kennedy was loathe

to risk an ‘incident’ resulting from the firing of his saluting cannon but

no admiral’s flag was discernible and the German’s guns were also trained

fore and aft. ‘I had well considered the question’, Kennedy admitted

afterwards, ‘and I believed that the salute was very likely to be the cause of

the German replying by shot and shell.’[42]

The ships passed in silence. Kennedy semaphored to Indefatigable,

‘Raise steam for Full Speed and then I am going to shadow her’, and then

sent a signal to Milne at 10.40 a.m.: ‘Enemy in sight. Lat 37°44’ N., 7°56’

E. steering E. consisting of Goeben

and Breslau.’[43]

Milne did not receive this message. When Indomitable signalled six minutes later, repeating that the enemy

was in sight and was being shadowed, Kennedy this time gave the position but

not

the direction in which the Germans were steering; Milne, who

did

receive this message, assumed they were still heading west. At 11.08 a.m. Milne

instructed Captain John Kelly in Dublin,

still at Bizerta, to inform the French Admiral that Goeben and

Breslau had

been found and ordered Kelly to proceed immediately to reinforce

Indomitable.

Meanwhile Chatham would proceed to

Bizerta to maintain communications with the French.[44]

Ten minutes later, Milne informed the Admiralty, ‘Indomitable,

Indefatigable sighted

Goeben, Breslau off Bona 10 a.m. They are

shadowed. Dublin ordered to assist.’[45]

This welcome news was received in

London shortly before 11 a.m. (GMT). Then, within minutes, a further signal was

received in which Milne passed on the report of a German collier waiting at

Palma for Goeben.[46]

Battenberg, as Milne had done, continued to look to the west, obviously unaware

that, within minutes, Milne would receive a further two signals from Captain

Kennedy both of which erroneously stated that Goeben

was heading north. Clearly in a quandary over this new information, Milne at

once sought clarification from Kennedy, which eventually arrived after midday

and, at last, correctly gave Goeben’s

course as east. Even so, to make absolutely sure that this was indeed the

correct course, Milne waited another couple of hours before notifying the

Admiralty.[47]

In the meantime, on the telegram reporting that the German ships were being

shadowed Battenberg minuted, ‘Very good. Hold her. War Imminent.

Goeben

is to be prevented by force from interfering with French transports.’ This

went too far for Churchill to authorize contravening, as it did, the undertaking

given to Asquith and Grey the previous night; Churchill therefore circled the

first three, two-word, sentences and noted ‘This to go now’, but the final

sentence would have to await confirmation.[48]

The truncated signal was sent at 11.20 a.m. (GMT) and was received aboard

Indomitable

with some disgust if only because they thought the message – apart from ‘War

Imminent’ – a waste of W/T: ‘the less one puts it to use the better.’[49]

Churchill immediately sought approval to send the second part of the order, but

this raised two questions: under what circumstances would the British be

justified in opening fire and, given that the Navy’s responsibilities were

global and not confined solely to the Mediterranean, when was the best time at

which Anglo-German hostilities should commence? The First Lord tackled the

second question after that morning’s Cabinet (at which it had been decided to

send an ultimatum to Germany to respect Belgian neutrality) by informing

Battenberg and Sturdee that an ultimatum would be sent and, as a consequence,

the German Ambassador ‘will ask for his passports’. Churchill wanted to know

at what time the rupture should take place: ‘At what hour of daylight or

darkness would it be most convenient for us to begin hostilities. Immediate

reply is necessary in order to put hour into the ultimatum.’[50]

Concerned that enough time should be allowed to make certain that the fleet was

at its war station, Battenberg minuted ‘Anytime after midnight tonight.’[51]

Seeking a judgment on the first

question Churchill approached Asquith and Grey at midday to inform them that

Goeben

and Breslau had been found ‘west of

Sicily’ and were being shadowed but it would be a great misfortune to lose

these vessels, as would be possible, in the dark hours:

Goeben was ‘evidently going to interfere with the French

transports’, the First Lord asserted erroneously, ‘which are crossing

today.’ Churchill informed them of the order that had already been sent to

hold Goeben and demanded an immediate

decision as to whether he could add the final sentence, ‘If

Goeben

attacks French transports you should at once engage her.’[52]

It would be another five hours before further news was received from Paris that

the transports would not sail, due to

the presence of Goeben,

and that the French Fleet had been given orders to bring

Goeben

to action ‘if possible’.[53]

Unaware of this French pusillanimity Churchill got his decision, with one

proviso: at Downing Street at 12.10 p.m. he ordered that Milne should be sent

the additional signal, ‘If Goeben

attacks French transports you should at once engage. You should give her fair

warning of this beforehand.’ This was immediately transmitted to Milne who

received it shortly after 5 p.m.[54]

The First Lord then returned to the Cabinet room to explain the situation to his

colleagues, presumably trusting that they would acquiesce in his

fait

accompli; however, as Grey had yet to telegraph the ultimatum to Berlin

(which would not go till 2 p.m.) the Cabinet refused to sanction any overt act

of war. Whether, if Churchill had had available the consul’s report from

Algeria concerning the damage caused by the German warships to the British

steamer Isle of Hastings, the Cabinet

may have decided differently is a moot point, but the First Lord was not overly

perturbed. In Asquith’s famous description: ‘Winston, who has got on all his

war-paint, is longing for a sea-fight in the early hours of to-morrow morning,

resulting in the sinking of the Goeben.’[55]

Churchill had no option but to

return to the Admiralty and telegraph new orders to Milne, just five minutes

after Grey at last delivered the ultimatum to Berlin:

from

Admiralty to All Ships at 2 p.m. (216 out)

The

British ultimatum to Germany will expire at midnight G.M.T. August 4th. No Act

of War should be committed before that hour at which time the telegram to

commence hostilities against Germany will be dispatched from the Admiralty.

Special

addition to Mediterranean, Indomitable,

Indefatigable sent at 2.5 p.m.

This

cancels the authorisation to Indomitable

and Indefatigable to engage

Goeben

if she attacks French transports.[56]

Milne

received one further important signal from the Admiralty which had been

dispatched from London during the fraught period between the confirmation of the

first sighting of the German ships and the Cabinet’s insistence that the time

period set by the ultimatum should first expire before any act of war could be

committed. This signal, superfluous but well-meant, would contribute to the débâcle

almost as much as Churchill’s ‘superior force’ telegram; this time

Battenberg was the chief culprit. The First Sea Lord had noted to Churchill on

the morning of the 4th that ‘In view of the Italian Declaration of Neutrality

(F.O. Rome, no. 156, 3.8.14) propose to telegraph C-in-C, Medn acquainting him

and enjoining him to respect this rigidly & not to allow a ship to come

within 6 miles of Italian Coast.’ Churchill took up the First Lord’s red

pencil and annotated ‘So proceed. FO shd intimate this to Italian Govt.’[57]

The order was sent to Milne from the Admiralty at 12.55 p.m. and Grey was

informed shortly afterwards.[58]

‘If this fact is notified to the Italian Government it should be made

clear’, Grey was pedantically enjoined, ‘that this order is inspired by a

desire to meet their views to the utmost, and is not to be taken as implying an

admission of their claim to territorial waters beyond the three-mile limit.’[59]

The crucial implication contained in

the order to Milne was that his ships were now effectively debarred from passing

through the Straits of Messina which were only two miles wide at their narrowest

point. This voluntary act of supererogation was unnecessary as Italy had already

declared her neutrality; neither the Italian Government nor the Foreign Office

in London had requested it; it conformed to no clause of the 1907 Hague

Convention; and it went further than required by international law, which merely

debarred belligerents from hostile actions within three miles of the coast.[60]

In the opinion of the British Naval Attaché in Rome not only was the order

unnecessary, it did nothing at all to increase the Italians’ opinion of the

British.[61]

To complicate matters further, less than two hours after Battenberg caused the

signal to be sent, Sturdee telegraphed to the Senior Naval Officer, Gibraltar

that the Straits patrol there was to include territorial waters.[62]

On the one hand it is easy to imagine the confused and strained atmosphere of

the first days of August, yet the war itself was not unexpected: at the

Admiralty, in particular, preparations should have reached an advanced stage

during the July crisis, however the work of the Naval Staff – while it was

perhaps too much to expect it to be faultless – was instead a shambles.

Churchill’s vaunted mission of 1911, the instigation of a smoothly functioning

staff, had failed.

On 1 August the scene in the War

Room was ‘wild, thousands of telegrams littered about & no-one keeping a

proper record of them.’[63]

A re-organization envisaged in April 1914 after two years’ experience was

hastily swept aside in August. At that time the War Staff proper numbered 33

officers which was not enough to deal with the emergency and which necessitated

a large and sudden intake once war appeared inevitable: six officers arrived

from the War College; another three who had previously been on half-pay; five

were seconded from other Admiralty Departments; but the largest number,

fourteen, were from the retired and emergency list. These additional officers

crowded into the War Room, operating in three watches around the clock. There,

with a moment to spare, an officer could stand at the window and gaze out to the

west, over Horseguards’ Parade, for the War Room was actually the First

Lord’s State Bedroom, situated on the first floor of Admiralty House. The

organizational structure in 1914 comprised the following sections:

A. British ships of war at Home and Abroad.

B. Patrol flotillas, trawlers, minesweepers.

C. (no longer existed)[64]

D. Colliers, oilers, fleet auxiliaries.

E1. Foreign war vessels (information from the Intelligence Division).

E2. Foreign merchant ships.

This

differed from the original 1912 organization in one important area: previously

the movements of British and foreign

ships had been dealt with by one section, depending on location.[65]

Now, the movements of Goeben and

Breslau

would be handled by one section while the movements of Milne’s ships would be

handled by another. These sections would, independently, mark up the positions

on large charts adorning the state bedroom as the information was received. The

relevant Naval Staff Monograph

comments, without a trace of irony:

The

system of 5 sections working in a single room broke down after a few days and

was abandoned, apparently for reasons of space. The system was not a good one.

Each section required a staff and apparatus of its own and the sections seemed

to have got in one another’s way. The Intelligence Sections, who followed

enemy movements, went off to another room and, though they came in and marked up

the War Charts, their exodus made immediate reference more difficult.[66]

Nevertheless,

by 4 August, an improvement had been made although it was still a strange way to

run a war, as Captain Dumas found out: ‘At last’, he recorded in his diary,

‘someone has taken in hand the organization of the war room and high time too

but it was an incongruity to go to Sturdee’s room and find him – the COS –

and Leveson – the DOD – having a tea party with their wives. Also which is

amazing there is a notice in Prince Louis’ office that no telephone message

must be sent to his house he has German servants.’[67]

One obvious problem concerned the

flood of telegrams pouring into the War Registry and overwhelming the staff of 3

resident clerks and 30 assistants (again divided into 3 watches). Some messages

were routine, many – in all probability – a waste of W/T, others of the

utmost importance; delay was inevitable but who could say that the message

waiting in the pile to be decoded was not vital and urgent?[68]

In addition, the Foreign Office was suborned to disseminate naval information.

As an example of the circuitous route a signal could take, at 9.10 on the

evening of 3 August the British Ambassador in Rome, Rodd, telegraphed the

Foreign Office that Goeben and

Breslau

had arrived at Messina on 2 August and were reported to have taken on board

1,000 tons of coal. This information reached the Foreign Office at 9.15 the

following morning, at which time George Clerk, the Senior Clerk at the Eastern

Department, minuted that the Admiralty should be asked by telephone whether it

would be of any use to repeat this, and similar telegrams, to Paris so that they

could be communicated to the French Ministry of Marine. Clerk’s motivation,

other than saving the Admiralty’s time, was that he was aware the ‘Toulon

Fleet is reported to be on the lookout for Goeben.’

The telephone call was duly made and resulted in a further minute: the Admiralty

asked the Foreign Office to send a paraphrase

of such telegrams to the French Embassy in London. This was done, and Cambon was

handed a paraphrase later the same day, presumably to pass on to Paris himself.[69]

Why allow clerks at the Foreign Office, with little or no experience of naval

affairs, to paraphrase information affecting naval strategy, with all the

contingent dangers that that entailed? And why then route the information

through the French Embassy?

Above all this chaos there strode

the figure of Churchill: jealous of his position; unwilling to delegate to the

Staff the functions which rightly belonged to them; unchecked by Battenberg and

Sturdee; drafting operational telegrams in his own hand and justifying this by

claiming the retrospective approval of the First Sea Lord and Chief of Staff

and, in doing so, applying the language of the politician to the orders to his

C-in-C. Battenberg did attempt to argue with Churchill on the afternoon of the

4th that immediate action should be taken against the German ships as, with

darkness approaching, they could escape in any direction but, bound by the

Cabinet, Churchill had gone as far as he could; besides, Battenberg’s own

telegram concerning the over-zealous deference to Italian neutrality would prove

a greater contributory factor to the escape than the decision to withhold

Milne’s authority to open fire.[70]

As Churchill and Battenberg remonstrated the German ships were, in any event,

drawing away from their shadowers, swallowed by the mist that had persisted

throughout the day.

The full extent of the degree of

centralization at the Admiralty in the early stages of the war was not revealed

until 1916: ‘…there grew at once on the outbreak of war a War Staff

Group’, Churchill then stated. ‘It consisted of the First Sea Lord, the

C.O.S., the Second Sea Lord and the Secretary, under the Presidency of the First

Lord. This group met daily, occasionally with additional members, usually for an

hour and a half or 2 hours, and examined the whole situation.’ Churchill

claimed the other Sea Lords were aware of what was going on, but this did not

tally with their recollection. Lambert, the Fourth Sea Lord, claimed that ‘in

the War Room where a lot of useful information could be got without bothering

people to look at telegrams, a list was put up on the door in Mr Churchill’s

own handwriting of people who were allowed to go in there and the Junior

Lords’ names were crossed out and the names of the civil members of the Board

were crossed out.’[71]

Churchill also admitted that ‘though in my time a large proportion of the

operative minutes and drafts of telegrams emanated personally from me, these

were the result not of my own knowledge alone, but they summed up and embodied

the results of daily consultations…’[72]

When asked by Admiral Sir William

May, at the Dardanelles Inquiry, whether the First Lord could give an executive

order to the Fleet without the Board knowing about it at all and, if so, whether

the order would be carried out, Churchill replied that it had never been done.

Pressed by May, he admitted that, theoretically, it may be done: ‘I suppose if

the First Lord said to the Secretary, Do so and so, the Secretary would send the

orders out and it would go to the Fleet, and the Fleet would of course obey it;

but I cannot conceive such a thing being done.’[73]

In effect, however, the Board of Admiralty had fallen into abeyance, to be

replaced by Churchill’s inner circle. When queried on this point, Fisher at

least was in complete agreement: the Board of Admiralty as a corporate body was

less consulted than before the war ‘because there was not the time to get all

these fellows together and to consult them. Besides, a junta is a bad thing for

a war.’[74]

The situation had become so bad that by 12 October 1914 the Junior Sea Lords

addressed a memorandum to Battenberg complaining that:

At

the beginning of the war, we were informed that it was not intended that we

should take part in councils of war. We preferred a verbal request to the

Secretary that reports on operations which may be rendered from time to time to

the Admiralty should be circulated to us confidentially for information. This

request has so far not been complied with. We do not want to raise difficulties

at this time, but we feel that it is wrong, that as naval members of the Board,

we should be kept in complete ignorance both of general policy adopted and also

of the decisions taken on proposals which are important but which in most cases

cannot be said to be either secret of confidential…

The

Sea Lords then requested that periodical meetings of naval members of the Board

be held at which they could be put in possession of important proposals[75]

however, by the end of that month, Battenberg himself had been relieved of duty

and Fisher – the arch centralizer – had returned. |

[1] Souchon, p. 484; Der Krieg Zur See, p. 39. According to Kopp, Two Lone Ships, p. 17, the Italians were concerned that the colliers might be battered against Goeben’s hull.

[2] Constantinople to Foreign Office, no. 396, 1 August 1914; von Mutius

to Foreign Office, 2 August 1914; Constantinople to Foreign Office, no. 408,

2 August 1914, in Max Montgelas and Walter Schücking (eds.), Outbreak

of the World War. German Documents collected by Karl Kautsky, (London,

1924), nos. 652, 683, 726, pp. 488, 505, 526 [hereinafter referred to as

Kautsky, German Documents]. Ulrich

Trumpener, The Escape of the Goeben

and Breslau: a Reassessment, The Canadian Journal of History, VI,

(1971), p. 173.

[3] Berlin to cruisers abroad, no. 11, 2 August 1914, Decode of Messages

sent in German VB cipher, PRO Adm 137/4065.

[4] Der Krieg Zur See, p. 40.

[5] Tirpitz, My Memoirs, vol.

II, p. 349.

[6] Secretary of State of the Imperial Naval Office to Secretary of State

for Foreign Affairs, 3 August 1914, Kautsky,

German Documents, no. 775, p. 552. Trumpener, Reassessment,

p. 173.

[7] Admiralty Staff of the Navy to Goeben, via Vittoria, no. 5, 3 August

1914, PRO Adm 137/4065; Kennedy, p. 5. The section in French does not appear

in the message as sent; presumably this was a French signal intercepted and

transposed with the German signal.

[8] The decodes can be found in PRO Adm 137/4065.

[10] Der Krieg Zur See, p. 39.

[11] Acting Consul-General, London to Sir Edward Grey, 5 August 1914, PRO

Adm 137/HS19.

[12] Admiralty Staff of the Navy to Secretary of State for Foreign

Affairs, 3 August 1914, Kautsky, German

Documents, no. 808, p. 569.

[13] C-in-C to R-Adl and Chatham,

2.59 a.m., 3 August 1914; R-Adl to C-in-C, 3.37 a.m.; C-in-C to R-Adl,

rec’d 4.23 a.m., NSM,B; Lumby, p. 150.

[14] R-Adl to C-in-C, 5.6 a.m., 3 August, NSM,B; W/T Signal Log, HMS Defence, IWM MISC 64 ITEM 1009.

[15] R-Adl to C-in-C, 6.50 a.m., 3 August, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 151; W/T

Signal Log, HMS Defence, IWM MISC

64 ITEM 1009.

[16] Log of HMS Chatham, PRO Adm

53/37560.

[17] C-in-C to Chatham and First

Cruiser Squadron, rec’d 8.27 a.m., 3 August, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 151.

[18] Court of Inquiry, qu. 5, Lumby, p. 248.

[19] C-in-C, Medt to Admiralty, no. 391, 3 August 1914, and minute by

Sturdee, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[21] See, Court Martial, qu. 120, Lumby, p.

288: Milne testified: ‘…looking over my war orders again, I saw that the

cruisers had to watch the mouth of the Adriatic. So I directed the

Rear-Admiral to return to watch the Adriatic.’

[22] C-in-C to R-Adl, 1st C.S., rec’d 2.33 p.m., 3 August 1914, NSM,B;

Lumby, p. 152; W/T Signal Log, HMS

Defence.

[24] Admiralty to S.N.O., Gibraltar, 2.45 p.m., 3 August; Admiralty to

C-in-C, 6.30 p.m., 3 August, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, pp. 152-3.

[25] Bertie to Grey, no. 127, rec’d 8.18 p.m., 3 August 1914, PRO Adm

137/HS19; Milne to Admiralty, 20 August 1914, para. 13, Lumby, p. 215.

[26] Note by Battenberg, Battenberg mss., IWM DS/MISC/20, reel 5, item

363b.

[27] Churchill to Asquith and Grey, for immediate action, 3 August 1914;

note by Sir William Tyrrell, WSC Comp.

vol. III, pt. i, p. 15.

[28] Corbett, Naval Operations,

vol. I, p. 59.

[29] Halpern, Naval War in the Medt.,

p. 24.

[30] Der Krieg Zur See, pp. 39-40.

[31] Court of Inquiry, Statement for the Defence, Lumby, p. 256. Note: the

allegation by Troubridge that Lapeyrère had sighted the smoke of Goeben first surfaced in a letter from Troubridge to Milne on 21

August. Troubridge maintained therein that, with the French fleet blocking

the way west, it was “certain” Goeben

was coming east. This would appear to be a clear case of hindsight. See,

Troubridge to Milne, 21 August 1914, Milne mss., NMM MLN 209/7.

[32] Court Martial, Statement for the Defence, Lumby, p. 369.

[34] On the basis of Troubridge’s dubious recollection alone, van der

Vat, p. 60, maintains that Goeben

and Breslau must have passed close

to the second group and so, therefore, were trapped between the second group

in the west and the first group in the east. As a result, Lapeyrère

‘could have encircled them’ but ‘deliberately threw away the

chance’. It is beyond doubt that, whatever Lapeyrère saw that morning, it

was not Goeben. At the cruising speed of the second group, which van der Vat

acknowledges was only 11 to 12 knots, it was over 150 miles away from the

closest position on the Algerian coast as Souchon completed his bombardment.

[35] Commission de la Marine de Guerre, quoted in Halpern, The

Naval War in the Medt., p. 26.

[36] Senior Naval Officer, Malta to C-in-C, (code time 0724 GMT), 4 August

1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 154.

[37] Milne to Admiralty, 20 August 1914, para. 17, Lumby, p. 215; C-in-C

to R-Adl, 1st C.S., (code time 0915), 4 August 1914, NSM,B, Lumby, p. 154.

[39] Dublin to C-in-C, (code time 0930), 4

August 1914, NSM,B, Lumby, p. 155.

[40] S.N.O., Gibraltar to Admiralty, no. 636, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm

137/HS19.

[41] Kennedy, p. 6, reports the sighting at 9.35 GMT (10.35 SMT), however

the ship’s log has 10.32 a.m. Log of HMS

Indomitable, PRO Adm 53/44830.

[42] Quoted in, E. Keble Chatterton, Dardanelles

Dilemma, p. 20.

[43] Kennedy, pp. 6-7; Indomitable

to C-in-C, 10.46 a.m., 4 August 1914, NSM,B, Lumby, p. 155; see also, Lumby,

p. 138.

[44] Indomitable to C-in-C, (0946); C-in-C

to Indomitable and Dublin,

(1008), 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 155.

[45] C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 394, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby,

p. 155.

[46] C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 395, ibid.;

Lumby, p. 156.

[47] Indomitable to C-in-C, (1015) and

(1034); C-in-C to Indomitable, (1039)

and reply by Indomitable (1110),

NSM,B; C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 396, (1329), PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, pp.

155-6, 159.

[48] Admiralty to C-in-C,

Indomitable, Indefatigable, no. 213, minute by Churchill, 4 August 1914,

PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[49] Narrative from the Indomitable: the escape of the Goeben,

Naval Review, 1919, vol. 12, p. 110.

[50] The ultimatum sent by Grey to Berlin at 2 p.m. was a bland document

requesting an assurance regarding Belgian neutrality by 11 p.m. G.M.T.,

otherwise the British Government would ‘take all steps in their power to

uphold the neutrality of Belgium…’ A reply was not expected and none was

forthcoming, so a second document was prepared for delivery to the German

Ambassador explaining that a state of war would exist by 11 p.m. An

incorrect version of this was delivered after it was mistakenly believed

that evening that Germany had already declared war on England and, when the

error was discovered, a correct version was substituted late that night by

Harold Nicolson, the son the Permanent Under-Secretary. See,

Nicolson, Lord Carnock, pp. 423-6.

[51] Churchill to First Sea Lord, C.O.S., minute by Battenberg, 4 August

1914, Nicolson mss., PRO FO800/375.

[52] Churchill to the Prime Minister, Sir Edward Grey, 4 August 1914, PRO

Adm 137/HS19.

[53] Bertie to Foreign Office, no. 132, 1.15 p.m., 4 August 1914 (rec’d

5 p.m.): ‘Following from Military Attaché:— It is hoped to bring from

Algeria a force of about 20,000; at present it is not deemed advisable to

commence transportation across Mediterranean owing to presence of German

warships; probable time for transportation 12 days; probable destination

neighbourhood of Belfort.’ Fifteen minutes later Bertie sent a dispatch

(no. 134) from the Naval Attaché which was also received in London at 5

p.m.: ‘French fleet have been given orders to bring Goeben

to action if possible. Goeben is

at present off Algerian coast.’ PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[54] Note by Churchill, 10 Downing Street, no. 214, 12.10 p.m., 4 August

1914, marked “for immediate action”, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[55] Asquith to Venetia Stanley, Asquith

Letters, 4 August 1914, no. 115, pp. 149-51.

[56] Admiralty to All Ships, no. 216, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

Note: Churchill was in error concerning the time of the expiration of the

ultimatum: it was timed to expire at midnight, Central European Time, which

was 11 p.m. G.M.T. This confusion over time zones is a common feature of the

saga of the escape, as will be shown.

[57] Battenberg to Churchill, minute by Churchill, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm

137/879. Cf. Churchill, World Crisis,

p. 133: ‘Bearing in mind how disastrous it would be if any petty incident

occurred which could cause trouble at this fateful moment with Italy...’

[58] Admiralty to C-in-C and Ad. Supt., Malta, no. 215, 4 August 1914, PRO

Adm 137/HS19, Lumby, p. 157.

[59] Admiralty to Foreign Office, 4 August 1914, PRO FO 371/2161/35790.

[60] Naval Staff Monographs (Historical) Fleet Issue, 1923, vol. VIII, The

Mediterranean, 1914-1915, para. 21, PRO Adm 186/618; Alfred Dewar, Winston

Churchill at the Admiralty, Naval Review, 1923, vol. 11, p. 226.

[61] W. H. D. Boyle, My Naval Life,

1886-1941, (London, 1942), p. 84.

[62] Admiralty to S.N.O., Gibraltar, no. 397, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm

137/HS19. Either there was a lack of communication in the Admiralty or, as

the Spaniards were not viewed as a problem, their territoriality could be

violated.

[63] Diary of Admiral Philip Dumas, entry for 1 August 1914, IWM PP/MCR/96.

[64] Originally, in 1912, section C handled intercepted W/T messages. A

new section was created for deciphering German signals — the famous

“Room 40”.

[65] In 1912 Section A dealt with HM ships and enemy ships in Home Waters

and section E with HM ships and enemy ships abroad.

[66] Naval Staff Monograph, The

Naval Staff of the Admiralty, Its work and development, (1929) Naval

Historical Library, pp. 56, 59-61.

[67] Diary of Admiral [then Captain] Dumas, entry for 4 August 1914, IWM

PP/MCR/96.

[68] Vice-Admiral Dewar, The Navy

from Within, (London, 1939), p. 163, gives the example of a cruiser

patrolling the Atlantic which wired, on 14 August, asking for Admiralty

permission to issue an extra ration of lime juice.

[69] Rodd to Foreign Office, no. 161, urgent, 3 August 1914; minute by

Clerk, 4 August, PRO FO 371/2161/35670.

[70] Martin Gilbert, Winston S

Churchill, 1914-1916, p. 30. Milne’s authority to open fire, if

granted, would have operated only in the case where the German ships were

physically interfering in the transportation of the French troops which, as

Souchon was steering east, they were patently not doing. If Battenberg’s

arguments that afternoon had prevailed it would, in all probability, have

been too late as, by the time the authorization had been relayed to the

battle cruisers, the German ships were almost out of sight.

[71] Evidence of Lambert before the Dardanelles Commission, qu. 4112, PRO

Cab 19/33.

[72] Dardanelles Commission, Statement by Churchill, War

Staff Group, PRO Cab 19/28.

[73] Proceedings of the Dardanelles Commission, qu. 1078-9, PRO Cab 19/33.

[75] Ibid., qu. 2956. Note: Sir Graham

Greene disagreed that there had been major changes after the outbreak of war

and maintained that the Junior Sea Lords could have found out what was going

on if they had wanted but, although they could read all the telegrams, they

were generally not consulted beforehand about policy decisions. He also

confirmed that the First Lord clearly had the right under Order in Council

to initiate orders: ibid., qu.

3032-3050.

|

|

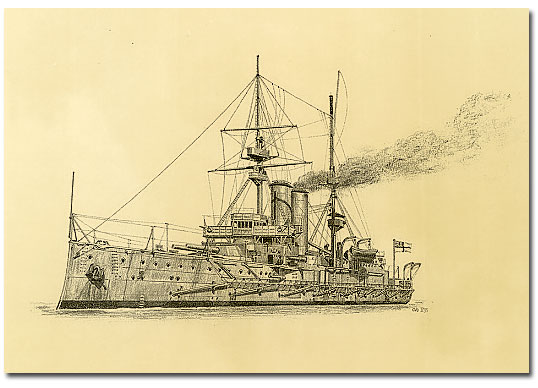

Ships of the Victorian & Edwardian Navy :

I have been drawing the ships of the

Victorian and Edwardian Navy for twenty

years for my personal pleasure and I am

including some of these drawings on this

site in the hope that others may find them

of interest.

The original drawings are all in pencil.

Reducing the file size and therefore the

download time has resulted in some loss of

detail.

A set of postcards

featuring eight of my drawings is now

available for £2.50, which includes postage

anywhere in the world.

For more

information please click on the drawing

below:

|

|

The Links Page :

As the range of our activities

is so diverse, we have a number of different

websites. The site you are currently viewing is

wholly devoted to the first of the three

non-fiction books written by Geoffrey Miller,

and deals specifically with the escape of the

German ships

Goeben and Breslau to the

Dardanelles in August 1914. The main Flamborough

Manor site focuses primarily on accommodation

but has brief details of all our other

activities. To allow for more information to be

presented on these other activities, there are

other self-contained web-sites. All our

web-sites have a

LINKS

page in common, which allows for easy navigation

between the various sites. To find out where you

are, or to return to the main site, simply go to

the

LINKS

page.

|

|

|

|

HMS Berwick

[Original artwork © 2004 Geoffrey

Miller] |

|

Geoffrey Miller

can be contacted by:

-

Telephone

- 01262 850943 [International:

+44 1262 850943]

-

Postal address

-

The Manor House,

Flamborough,

Bridlington,

East Riding of Yorkshire, YO15 1PD

United Kingdom.

-

E-mail

-

gm@resurgambooks.co.uk

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|