|

|

|

|

|

|

SUPERIOR FORCE

: The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of

Goeben and Breslau

© Geoffrey Miller |

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 4

|

|

The Chase Begins

|

|

|

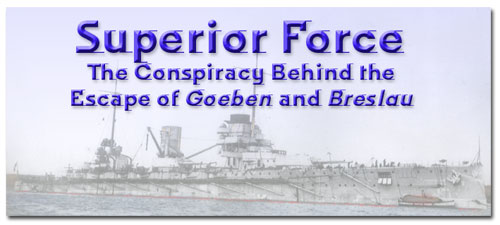

HMS Indomitable

photographed chasing SMS Goeben, 4 August 1914 |

Having

feinted north-west after the bombardment, Souchon now followed his orders of

some hours previously and put Goeben

about to shape course east, for the Dardanelles. The continued boiler problems,

allied to the inability to obtain sufficient coal at either Brindisi the

previous Saturday or Messina on Sunday, put paid to any idea of a non-stop run;

Souchon would have to obtain coal again and the obvious location to do so,

notwithstanding the difficulties that would inevitably be raised by the Italian

authorities, was Messina. |

|

However, no sooner had

Goeben rejoined

Breslau

shortly after 10 a.m. on Tuesday 4th than the British battle cruisers were

sighted, heading west at speed. In Souchon’s words, ‘we ran straight into

the British lion’s jaws.’[1]

The last official communication he had received regarding the attitude of

Britain had been sent as long ago as 6.12 the previous morning; and this had

only warned him superfluously to ‘Be prepared for hostile actions on the part

of English forces.’ Although Souchon ordered action stations he admitted that

he dare not open fire as he was not sure whether Britain was then an enemy; the

guns of his battle cruiser also remained in their securing positions, fore and

aft. Breslau, meanwhile, caught on the

opposite bow of the British ships was ordered to clear to the north-east at

maximum speed.

As

Indomitable

and Indefatigable turned to begin their stern chase Souchon realized

that his only realistic chance of escape lay in concealing his boiler defects

from the British and, by some means, making Goeben

live up to her reputation as the fastest ship in the Mediterranean.

Goeben

was making only 17 knots at the time of the sighting and the speed that Souchon

would later require could only be achieved by superhuman effort on the part of

his crew. By midday, she was making 22.5 knots and, in short bursts, 24 knots.

Goeben resembled nothing so much as a giant metal beehive where,

deep inside, the workers laboured furiously to satiate the appetite of their

Queen, in this case the 21 serviceable boilers (3 of the 24 were out of action)

feeding the steam to the turbines. Pressed into this enervating service, a W/T

operator, Georg Kopp, has left the following account:

The

whole ship’s company, in so far as they were not indispensable for the guns or

for duty on the bridge, were ordered to the bunkers and stokeholds to trim coal.

Stokers, seamen, under-officers, midshipmen, officers, the whole personnel

worked at trimming coal, stoking, and clearing the ash. The overheated air

affected lungs and heart. Shut off from the outer air by the armoured deck, we

worked in the compressed atmosphere forced down through the ventilators. The

coal in the neighbourhood of the boilers had to be left. That in the outlying

bunkers was trimmed first, and in view of the great length of the ship these

were often a long way from the boiler room.

There was an infernal din

going on in the interior of the ship. The artificial draught roared and hissed

from above the stokeholds, drove into the open furnace doors, fanning the

glowing coal, and swept roaring up the smoke-stacks. In the engine-room there

was the whir of the turbines, revolving at ever increasing speed; the whole ship

trembled and quaked. The Goeben was going all out…[2]

As

already related, after failing to receive Indomitable’s first sighting signal, which correctly identified

the course as east, Milne then received the second which did not indicate

direction while the third, which was in his hands by 11.44 a.m., erroneously

gave Goeben’s course as north. This

faulty information was repeated in a further signal ten minutes later. It was

not until 12.10 p.m. that a signal was sent by Indomitable

and received by Milne giving Goeben’s

correct course — east.[3]

By that time Breslau was out of sight

to the British though they inferred, by the strength of her W/T signals, that

she was still close. One difficulty, perhaps not fully appreciated by Milne

whose flagship, Inflexible, basked

under a cloudless sky in the Malta Channel,[4]

was the lowering haze which proceeded to thicken as the chase progressed. The

British ships had originally begun the chase with Indefatigable

astern and port of Indomitable but, in

this position, she was being fouled by the billowing acrid black smoke pouring

from Indomitable’s funnels. Captain

Kennedy thereupon ordered Captain Sowerby to go through the smoke and form

single line abreast to port. If the haze continued to thicken he was prepared to

order each ship to close up on one of Goeben’s

quarters and, indeed, at one point the opposing ships were just 6,500 yards

apart, a fact which worried Kennedy as he believed it was well within the

German’s torpedo range. Even so, there were other matters for Kennedy to

consider: ‘At the suggestion of Captain Sowerby, his ship’s and

Indomitable’s

ship’s companies went to dinner at separate times, the one not at dinner being

of course at action stations.’[5]

At 2.20 p.m.

Breslau

was again sighted closing Goeben from

the north; when joined up, the two German ships began to zigzag. Kennedy’s

attention now turned to mines, which he suspected the Germans might drop astern:[6]

he signalled Indefatigable to keep

clear of the wake of the German ships.[7]

Shortly after Breslau rejoined

Goeben,

Kennedy was reinforced by the light cruiser Dublin

which had been at Bizerta delivering Milne’s letter to the French and had then

been ordered to join in the chase as soon as the first sighting had been made.

While on route, Dublin forwarded the

latest information held by the French which reiterated their belief that a

collier awaited the German ships at Palma.[8]

Milne had, of course, received a similar report from Dublin

some hours earlier and, as shown, had communicated the information regarding the

putative collier to the Admiralty. By mid-afternoon, however, with

Goeben

now confirmed on an easterly course for some hours, the second report from

Dublin

caused Milne to ponder. Searching his charts, he discovered the Gulf of Palmas

on the southern tip of Sardinia, and just 70 to 80 nautical miles north of

Goeben’s

current position. From that location, Goeben

could coal and be ready to launch a further attack on the French North African

coast or the transports; it was an original idea, even if borne out of

desperation, and Milne sought verification by questioning

Dublin’s Captain as to whether he meant ‘Palma’ or

‘Palmas’? Back came the dispiriting reply, ending any doubt, ‘Palma —

Majorca’.[9]

Writing in 1923, Admiral Alfred

Dewar was able to state, using the full benefit of hindsight, that

Dublin’s

second report of the collier ‘was one of these vague messages which a

practised Intelligence Officer learns to view very sceptically.’ But this

ignores the fact that Milne had received next to no intelligence that day; had

no real idea what the French were doing; had acted on Admiralty orders in

dispatching the two battle cruisers westward; and had been instructed that his

first duty was to protect the French transports yet was unaware they had not

sailed. In the circumstances it is not surprising that Milne would snatch at any

intimation as to Souchon’s intentions.[10]

Captain Kennedy, writing earlier than Dewar but also not afraid to avail himself

of hindsight, thought the collier story ‘a yarn’ which fitted in with the

feint north-west after the bombardment and was concocted for the benefit of the

French; he was more anxious that Breslau might send ‘a W/T to some collier to meet them on the High

Seas or Sardinia Coast.’[11]

When

Dublin

joined up with the battle cruisers Kennedy positioned himself astern of

Goeben in Indomitable,

kept Indefatigable to port and placed

Dublin

to starboard. During this time the two German ships kept separating and

rejoining in an attempt to confuse their shadowers as to their intentions until,

at 4.45 p.m., Dublin at last saw her

chance — by this time the German ships had pulled away from the British battle

cruisers but not the faster light cruiser. Captain John Kelly on

Dublin observed that

Breslau

had parted company again and immediately flashed a signal to the C-in-C and

Kennedy: ‘Shall I engage her?’ Milne responded with alacrity, with an

emphatic “No”, which was repeated by Kennedy also, who was concerned that

the Germans might be trying to get between the light cruiser and himself.[12]

Ten minutes after his alarming signal, Kelly reported that

Goeben

and Breslau had joined up once more, but by 5.20 they had separated

again, this time with Goeben

apparently going northward and Breslau

to the south-east.[13]

In fact Souchon had detached Breslau

with orders to proceed to Messina ahead of him and make arrangements to take on

board 1,500 tons of coal. Souchon also telegraphed to his Embassy in Rome to

request that they support his application to take the authorized quantity of

coal on board as the permission granted by the Italian Minister of Marine on the

2nd had arrived so late in the day it had not been used.[14]

As

the distance between the two German ships increased Dublin

signalled for instructions; Kennedy had no hesitation in ordering her to shadow

Goeben – ‘the most important item in our programme’ – on the

basis that, while many of the British ships in the Mediterranean could deal with

Breslau, only the three battle

cruisers could hope to scrap successfully with Goeben.[15]

In case Breslau should be attempting

to escape around the south of Sicily, Milne dispatched two light cruisers (Chatham

and Weymouth) to guard the passage

between Graham’s Shoal and the African coast and shadow

Breslau if seen.[16]

Meanwhile, as Dublin continued to

chase Goeben, it was obvious that

Indomitable

and Indefatigable had not been able to

keep up even to the German’s reduced speed: what had gone wrong?

Indomitable,

originally capable of 26 knots, was certainly overdue for a refit and just as

important in Kennedy’s opinion was his belief that she was deficient by some

90 stokers. Even using fuel oil in addition to coal, Kennedy calculated that he

needed these additional men (divided into three watches of 30 each) to trim

coal, yet the only recourse he had was to denude the gun crews which would leave

him vulnerable if Goeben suddenly

turned to engage. At 4 p.m., as Goeben

disappeared from view, Kennedy ordered down to his engineers to go as fast as

they possibly could; it was not enough. Furious, he signalled Milne, ‘Germans

are running away from me, steering east; speed 26 knots to 27 knots. 90 coal

trimmers are urgently needed by these ships although we are using oil fuel.’[17]

The average speed of Goeben that

afternoon had actually been only 22 knots, with up to 24 knots available in

short bursts; the British ships should have been capable of 22 knots at least,

in which case the difference on the day was not so much one of metal and

machinery as of toil and sweat. The contrast between the unrelenting labour on

Goeben

and the watches proceeding to tea at intervals on Indomitable

and Indefatigable is vivid.

Unfortunately, Kennedy’s signal perpetuated the myth that

Goeben

was a good 3 knots faster than any British ship capable of successfully engaging

her — how had this mistake occurred?

By late afternoon on 4 August the

mist had formed banks in places, some of which were extremely thick. In these

conditions Goeben could disappear from

sight very quickly, perhaps giving the impression that she was travelling faster

than she was; in addition, there remained the unstated assumption borne by every

man on board the British ships that Goeben

WAS faster, which would also tend to make them over-estimate her speed. On the

other hand it was only a scant two days earlier that, when Kennedy asked his

question at the officers’ meeting aboard Defence

– ‘How is it proposed that 22 to 24 knot ships shall shadow 27 to 28

knot ships that don’t want to be shadowed?’ – no-one else took this

seriously and Troubridge answered for all by declaring to the assembled company

that it was common knowledge ‘that Goeben

was drawing a foot and a half over her proper draught and so could not nearly

steam the speed she was supposed.’ Could it be that Kennedy was attempting to

show that he had been right all along?

Once

Goeben

was lost from view Kennedy’s thoughts turned to what he would do next: he had,

by now, correctly formed the impression that Goeben

was heading for Messina and, with this in mind, about 5 p.m. he approached his

navigator, Lieutenant-Commander Tindal. Kennedy intended that night to form his

three ships in line abreast, with Dublin

in the centre, and at the maximum distance apart, depending on visibility, and

to patrol between the southern tip of Sardinia and the north coast of Sicily.

Then, at daybreak, he would sweep east and position himself off the northern

entrance of the Straits of Messina presuming also that Milne, in

Inflexible,

would take up a corresponding position off the southern entrance.[18]

Kennedy had already started to carry out the first part of his plan – the

north/south patrol – when, at 6.40 p.m., Milne signalled, ‘Dublin

endeavour to keep in touch with Goeben.

Indomitable and

Indefatigable

slow speed, steer west.’[19]

Soon after, Milne enlarged on this order: ‘Goeben may turn westward during the night, steering Majorca where

his collier is. Shape course accordingly. Dublin

may be able to keep you informed.’ However, this last proved a false hope with

the receipt of Dublin’s forlorn

signal at 7.20 p.m., ‘Goeben out of

sight now, can only see smoke; still daylight.’[20]

Kennedy obediently turned the battle cruisers around, slowed to 7 knots and

plodded back westwards. He did not attempt to remonstrate with Milne: anyone who

knew the C-in-C, he wrote abjectly, was aware that ‘he will never alter an

order, and not only will he not alter an order but he gets angry at even being

asked to do so; besides, for all I knew he might have more information about the

Germans’ and also about the Italians’ intentions than I had.’[21]

Milne telegraphed his new dispositions to the Admiralty where they were received

at 7.58 p.m. (GMT) with the simple comment, ‘no action proposed’.[22]

During that evening Milne received

the official War Telegram instructing him that hostilities would commence –

against Germany only – at midnight, GMT, (the wrong hour due to the confusion

in London: the ultimatum actually expired at midnight Berlin time, or 11 p.m.

GMT; the mistake was Churchill’s and, fortunately, it made no difference).

Troubridge, patrolling the Adriatic, was naturally anxious regarding the

attitude of Austria but Milne had no further information to pass on to him

except that, for the time being, Britain was not at war against Austria; however,

the receipt of the War Telegram seems to have concentrated Milne’s mind. For

some hours, while Dublin continued to probe eastwards in the darkness following the

last known course of Goeben,

Indomitable

and Indefatigable had been patrolling between Sardinia and Sicily at 10

knots after Kennedy’s enforced change of course.[23]

The C-in-C decided that now was the time to gather his forces together so, just

after midnight, his flagship Inflexible shaped course north-west at 10 knots with the objective

of picking up the two light cruisers, Chatham

and Weymouth, which had been

patrolling off the African coast and then ultimately effecting a rendezvous with

Indomitable and

Indefatigable

to the west of Sicily. Troubridge’s First Cruiser Squadron would continue to

watch the Adriatic, with the exception of the light cruiser

Gloucester

which was detailed to watch the southern entrance of the Straits of Messina.[24]

At 1 a.m. (local time) on the night

of August 4/5, at which time Milne thought the war had just begun, the situation

was as follows: Goeben and

Breslau, on the

north coast of Sicily, were proceeding independently east to Messina;

Dublin

had now given up the chase and had been recalled to join the two battle cruisers

west of Sicily, a position Milne was also heading for in his flagship,

accompanied by two light cruisers; Troubridge’s division patrolled the

Adriatic; and a lone light cruiser, Gloucester,

proceeded to watch the southern exit of the Straits of Messina. In so framing

his dispositions, Milne was clearly still looking west. ‘My first

consideration’, he wrote later that month,

was

the protection of the French transports from the German ships. I knew they had

at least 3 knots greater speed than our battle cruisers and a position had to be

taken up from which Goeben could be

cut off if she came westward. I considered it improbable that

Goeben

would try to pass north of Corsica as she would believe the passage to be

watched by French Cruisers, nor would she pass through the Straits of Bonifacio

owing to the danger from French submarines and destroyers. She would, therefore,

if going westward, pass south of Sardinia and I knew that a German collier was at Palma, Majorca.[25]

The

information received in London earlier in the night that the French transports

had been delayed does not appear to have been relayed to Milne. Additionally,

Battenberg’s unfortunate order regarding Italian neutrality effectively barred

Milne’s ships from Messina and, it has been argued, could have strengthened

his belief that Goeben and

Breslau would

break west once more.[26]

By the dispositions so adopted Milne

would have been able to prevent Goeben

and Breslau escaping west, through Gibraltar, or doubling back on their

tracks to go south of Sicily while, if they did actually proceed to Messina and

then emerged south through the Straits, where could they go? Troubridge barred

the entrance to the Adriatic, Suez could easily be blocked (or so it was

thought),[27]

and the Aegean was no more than a cul-de-sac from which it would be doubtful if

they could re-emerge. Indeed Milne’s last remaining worry that night concerned

Austria and was probably accentuated by Troubridge’s earlier signal to him.

Milne inquired of the Admiralty, ‘Is Austria Neutral Power?’ — a signal

not received in London till 7.55 on the morning of the 5th. It was not then

until after midday that the reply, drafted by Battenberg, was dispatched:

‘Austria has not declared war against France or England. Continue watching

Adriatic for double purpose of preventing Austrians from emerging unobserved and

preventing Germans entering.’[28]

The clear implication in this signal, as far as Troubridge was concerned, was

that he was not to tackle the Austrians, merely to make sure they were observed

if attempting to leave the Adriatic, but there was no such prohibition regarding

the Germans who were to be prevented from entering. The long shadow of Churchill’s

“superior force” telegram of 30 July was cast over this message as Milne’s

general orders to all ships, issued the previous night, had instructed

Troubridge to watch the entrance to the Adriatic but ‘not to get seriously

engaged with superior force.’[29]

Battenberg’s signal should have conveyed his intention that

Goeben

and Breslau were to be attacked – at least if they attempted to effect

a junction with the Austrian fleet – but when read together with Milne’s

earlier signal Troubridge was apparently left with some discretion at to what

exactly constituted a superior force. Battenberg’s signal was interesting also

as being the first hint from the Admiralty, however slight, that the German

ships might continue to sail east.

Milne effected his own concentration

late on the morning of Wednesday 5th, just to the north of Pantellaria. The only

excitement in the group centred on Chatham

which, earlier that morning, had obtained a prize — the German steamer

Kawak

of Hamburg. Once the rendezvous was made the steamer was turned over to a

destroyer and Chatham took her patrol

station, 8 miles from the flag, at 15 knots.[30]

Captain Kennedy was unhappy with Milne’s choice for the rendezvous as they

were within sight of any German spy on Pantellaria and he thought ‘that the

Goeben

would very soon hear by cable to Vittoria [Sicily] and thence by W/T of the

concentration of our three battle cruisers, Dublin,

Weymouth and Chatham, and that

they [the British ships] were off to the Westward.’ Despite this private

doubt, when Milne asked Kennedy to come on board Inflexible

to discuss the situation and try to pinpoint the exact location of the German

ships, Kennedy remained convinced they were somewhere off the north coast of

Sicily ‘where they could easily coal.’[31]

Coal was also becoming a problem for

Milne — at the end of the chase the previous evening

Indomitable

had reported 2,130 tons remaining (approximately two-thirds of the maximum 3,083

tons); however, it was not evenly distributed throughout the ship’s four main

boiler rooms, and boiler room B in particular (housing 8 boilers) was short.

Because of this Kennedy could not guarantee full speed for more than 30 hours.

Milne therefore took the opportunity of sending Indomitable

to nearby Bizerta for the dual purpose of coaling and maintaining contact with

the French. The C-in-C also decided to accompany Indomitable in his flagship,

Inflexible,

to give the French a morale boosting minor demonstration: as the imposing

squadron approached the French port Inflexible

fired a salute, hauled out and proceeded back north to the patrol line with the

remainder of the squadron (with the exception of Dublin which had been dispatched to Malta to coal that afternoon).

Meanwhile, Indomitable steamed into

the harbour amidst prolonged cheers from the French crews and inhabitants lining

the shore.[32]

Souchon’s

entrance into Messina was an altogether more sombre affair, full of foreboding.

During the night’s run north of Sicily Goeben

encountered a flotilla of torpedo boats which set alarms ringing until they were

revealed in the bright moonlit conditions as belonging to Souchon’s erstwhile

ally, Italy; the battle cruiser held her fire and was warily escorted into

Messina harbour, arriving at 7.45 on the morning of Wednesday, 5th.

Breslau

had arrived some 2½ hours earlier.[33]

Coaling commenced at once, though it soon became apparent to Souchon that the

exhaustion of his men, coupled with the difficulties of coaling with inadequate

facilities from steamers better adapted to taking in coal rather than giving it

out, meant that he would not be able to fill his bunkers in the time allotted by

the Italians.[34]

Half a dozen steamers in the harbour were raided for their coal,[35]

the hot filthy work continuing throughout the day and being made more unbearable

by the shimmering heat of a still August day.

By virtue of her earlier start,

Breslau

had quickly come to the attention of interested onlookers in her efforts to

obtain coal and by 11.30 a.m. Rennell Rodd, the British Ambassador in Rome, had

been privately informed that the German cruiser was attempting to procure coal

from a British collier.[36]

This was the humble Wilster carrying a

load of Welsh coal for the German-owned firm, Hugo Stinnes. When she had arrived

at sunset the previous day, Britain was still at peace; at 8 o’clock on the

morning of Wednesday 5th her master, Captain Eggert,[37]

was coming ashore in his boat when he saw Goeben anchoring nearby: he was now facing the enemy.[38]

Rodd telegraphed at once to the consul in Messina to warn Eggert not to supply

coal to belligerents, and forwarded the information to London where it was

received at 6.30 p.m.[39]

He also made a representation to the Italian Foreign Office and was informed

that, upon Breslau’s arrival, a

German collier was directed to the inner port by the Italian naval authorities

to allow Breslau to load sufficient

coal to take her to the nearest port. In reporting this to the Admiralty in the

early afternoon of the 5th, Rodd added his own suspicion that

Goeben

also was at Messina, information which was then unknown to anyone on the British

side.[40]

Grey’s reply the following day instructed the Ambassador to represent to the

Italians that Goeben should leave

Messina within 24 hours and must not be permitted to receive coal in any other

Italian port.[41]

Grey’s demand came too late.

However, the Italians had, on their own initiative, already presented Souchon

with an ultimatum without prodding from the British Foreign Secretary. The

German commander had received a deputation of four Italian officers on the

evening of the 5th who proceeded to deliver notification that his stay in port

be limited to 24 hours: other than pointing out that the limitation was a

‘British presumption’ Souchon reconciled himself to having to leave the

following day — in all probability before coaling was completed. The best he

could do was to have the 24 hour period commence when he had actually received

permission to coal, which had not been until 3 p.m. on the 5th, some seven hours

after he had arrived.[42]

To make up the shortfall Souchon wired his agent in Athens and requested him to

dispatch a collier with 800 tons to rendezvous with Goeben

and Breslau at Cape Malea; a further collier would be dispatched from

Constantinople to Santorin, while a third would wait off Chanak, at the entrance

to the Dardanelles. Although the German ships would take in 1,580 tons as a

result of their labours in Messina it would either be insufficient to get them

to the Dardanelles if they had to steam at high speed or would leave them

perilously short of coal should, for some reason, their entrance to the

Dardanelles be delayed. ‘Everything’, Souchon later wrote, ‘depended on my

being able to obtain enough start on the pursuing British to enable us to coal

en route, and that we could find at least one of the colliers ordered to meet

us.’[43]

The ships’ crews toiled throughout

the night: holes were cut in the steamers’ decks to allow easier access to

their precious cargo, in this case, foul, poor quality coal. Upon

Goeben

and Breslau the ships were prepared

for action: wooden and inflammable gear was stripped and removed. Crowds

gathered to watch the excitement and participate vicariously in the drama.

Souchon described,

Ragged

hawkers of fruit, sweetmeats, picture postcards and curios of all kinds,

strolling musicians and singers with mandolines, pianos and castagnettes,

carabinieri, harlots, monks, soldiers, nuns, and even a few well-dressed people

continually tried to beg our semi-nude, coal-begrimed lads for a souvenir of

some kind…[44]

Detached

somewhat from the organized chaos Souchon had time to contemplate the latest

cables; the news was not good. Of the three cables sent to him on the 5th by the

Admiralty Staff, the second and third intimated what Souchon must have already

known — he could not count on the assistance of the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[45]

It was the first cable, however, which did not reach Souchon till 11 a.m. on the

6th, that contained the bombshell: ‘It is impossible to put into

Constantinople at present for political reasons.’[46]

For all his resolve, it is hard not to imagine that, if only for a split second,

the thought flashed through Souchon’s mind that he had now trapped himself:

cut off from escape to the west by Milne and the French, Italy neutral, the

Adriatic patrolled by Troubridge, and now it was not possible to put into

Constantinople.

The first hint at the Foreign Office

in Berlin that all was not proceeding smoothly in Constantinople was received

just after midnight on 3/4 August. Enver Pasha, the Turkish Minister of War,

abetted by General Liman von Sanders, head of the German Military Mission, had

wanted to declare war on Russia immediately in order to seize three valuable

Russian steamers lying in the Bosphorus. The Grand Vizier, as was his wont, was

unhappy — particularly as Bulgaria’s attitude had not been determined (come

to that, the Grand Vizier was not exactly enamoured of a war with Russia at

all). Ambassador Wangenheim, who had been ordered to overcome his scruples

regarding Turkey’s value as a potential ally, succeeded in cooling Liman’s

ardour for the time being, while Wilhelm instructed that efforts should be

hastened to bring Bulgaria into the fold.[47]

At 9.30 on the evening of the 4th a further cable was received in Berlin from

Wangenheim:

Enver

lets me know that the military authorities of the Dardanelles have been

instructed to let Austrian and German war-ships enter the Straits without

hindrance. Grand Vizier fears, however, that if use is made of this privilege

before the relations with Bulgaria have been settled, an acceleration of

developments not desired at the present time by Germany or Turkey might be the

result.[48]

The

apprehensions of the Grand Vizier were removed by 6 August when a limited

alliance was concluded with Bulgaria, but pressure on the cables prevented news

of his change of heart reaching Berlin in time to notify Souchon before he

sailed from Messina. Then, when the vital signal – ‘It is of the greatest

importance that you should enter the Dardanelles as soon as possible’ – was

at last dispatched from Berlin on the 7th, Souchon failed to receive it.[49]

Souchon was getting scant direction

from his Admiralty Staff compared to Milne’s surfeit; yet this was not

entirely to his detriment. Milne’s problems were exacerbated by superfluous

telegrams from London, coupled with the failure to pass on information which

would have been of use to him, whereas Souchon was left, more or less, to make

his own decision. The official German history credits Souchon with having ‘a

firm grasp of the political situation’ which, added to his personal

acquaintance with prominent Turkish political figures, led him to believe that

the outlook was ‘favourable for drawing Turkey into the war on our side, if he

succeeded by entering the Dardanelles with the two German cruisers in placing

her in such a position of constraint as must lead to a breach of her

neutrality.’[50]

In fact, it seems that it was not this laudable, if faintly doubtful, prescience

but the failure of the Austrians to lend active support that was the vital

consideration: by entering the Adriatic, and thereby becoming dependent on the

support of the Austrians, Souchon realized he would be ‘condemned to

inactivity’ by the defensive posture his allies had adopted.[51]

In late July both the Italian and Austrian navies had quietly prepared for

mobilization, with a slim possibility that the grandiose scheme of the 1913

Triple Alliance Naval Convention might actually achieve fruition. This hope was

dashed when, on the last day of July, Admiral Haus, the Austrian C-in-C who was

to assume overall command, learned that the Italian Foreign Minister considered

the war declared by Austria against Serbia three days previously to be one of

aggression, thereby relieving Italy of the necessity to adhere to the Triple

Alliance, which was principally a defensive treaty. On 1 August Haus was

informed that, should Italian neutrality be confirmed, the Austrian fleet would

be confined to the Adriatic.[52]

Souchon’s pleas for help must have

been a bitter blow to the ailing Austrian Admiral. Early on the morning of the

5th, before arriving in Messina, Souchon had wired the German Naval Attaché in

Vienna to request Austrian assistance and, shortly after, Souchon himself made a

direct approach to Haus: ‘Urgently request you will come and fetch

Goeben

and Breslau from Messina as soon as

possible. English cruisers are off Messina, French forces are not here. When may

I expect you to be near Messina, so as to sail?’[53]

Haus was confronted with a set of insuperable problems. He knew, from his

intelligence, that the French fleet had sailed and assumed that they would be on

their way to support the British at Messina; with the start they had had, the

French would arrive before the Austrian fleet, especially as the Austrian

mobilization had not yet been completed. The combined Anglo-French force would

be superior to the Austrian, so that Haus risked the sacrifice of his fleet

without the certainty of aiding Souchon. Even when assured by the German Naval

Attaché that the French remained in the western Mediterranean Haus was left

with a further prohibition, this time of a political nature: Britain and Austria

were not as yet at war, a situation which (for the present) was amenable to both

sides, but particularly the Austrians. In an attempt to maintain this fragile

and illusory state of affairs the Austrian High Command ordered on 5 August that

hostile action against British ships was to be avoided, yet virtually any effort

to come to Souchon’s aid was likely to involve a clash against either

Troubridge’s or Milne’s forces.[54]

By 6 August Souchon was resigned to

the fact that he was on his own; all he had to cling to was the fact that the

cable received that morning only prohibited his entry into Constantinople

for

the moment – the ‘political reasons’ that had made it impossible to

proceed there ‘at present’ could always change as indeed they were in the

process of doing. Souchon had already framed his sailing orders regarding the

passage east when the prohibition arrived; he did not alter them.

(1) Intelligence of the enemy indefinite. I assume that enemy forces are in

the Adriatic, and that both exits from the Straits of Messina are watched.

(2) Intention: to break-through to the eastward and try to reach the

Dardanelles.

(3) Execution:

Goeben leaves 5 p.m.

[6 August] speed 17 knots. Breslau

follows at a distance of 5 miles, closes up at dark. I shall at first try to

create the impression that we wish to proceed to the Adriatic, and if that seems

to be successful, attempt during the night, by a surprise alteration of course

to the right, to gain a lead towards Cape Matapan at full speed, and if possible

shake off the enemy.

(4) A collier requisitioned by me ought to be lying from 8th August onwards

at Cape Malea; further, from the 10th August, one 20 miles S. of Santorin and

one at Chanak.

(5) The steamer

General is to leave

at 7 p.m., close under the coast of Sicily and try to reach Santorin. If she is

stopped she is to report the fact by W/T if possible. If she receives no further

orders from me, she is to ask Loreley

for them (telegraphic address “Bowalor Constantinople”) on the second day of

her stay at Santorin.

(signed) SOUCHON.[55]

Coaling

on the German ships stopped shortly afterward; as his men were now near complete

exhaustion, Souchon allowed time to rest and bathe before they sailed.

Additional eager volunteers were also recruited amongst the merchant seamen in

the port to bring the ships up to their prescribed wartime complements. As the

ships sailed late that afternoon the crowds that had come to gaze now cheered. |

[2] Georg Kopp, Two Lone Ships,

(London, 1931), p. 30. Note: Kopp is useful for ancillary colour but his

account is shot through with factual errors.

[3] Indomitable to C-in-C, (code time 1015

— note, this is always in GMT); Indomitable

to C-in-C, Dublin, (1034); C-in-C

to Indomitable, (1039) and reply

by Indomitable (1110); NSM,B.

Lumby, pp. 155-6.

[4] Ship’s log, HMS Inflexible,

4 August 1914, PRO Adm 53/44838.

[6] It will be recalled that when visited by a British officer at Durazzo, Breslau was seen to be carrying

mines.

[8] Admiral, Bizerta to C-in-C, via Dublin,

(1145), 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 157.

[9] C-in-C to Dublin, reply by Dublin,

(1515), 4 August 1914, NSM,B.

[10] Alfred Dewar, Winston Churchill

at the Admiralty, Naval Review, 1923, vol. 11, p. 225.

[12] Dublin to C-in-C, Indomitable,

(1545) 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 158.

[13] Ibid., (1555), (1620), NSM,B; Lumby, p.

159.

[14] Goeben to Baron Grancy, Embassy Rome,

urgent, no. 5, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/4065.

[16] C-in-C to Chatham, Weymouth,

(1735) 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 161. Milne later claimed that he had

taken this action in case either Goeben

or Breslau had broken back

southward. See, Milne to Admiralty, 20 August 1914, Lumby, p. 216.

[17] Kennedy, p. 8. Indomitable

to C-in-C, rec’d 4.10 p.m., 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 160.

[18] Deposition by Lieutenant-Commander Tindal, 17 November 1914, Kennedy

mss., Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives.

[19] C-in-C to Indomitable, Indefatigable, Dublin,

(1740) 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 162.

[20] C-in-C to Indomitable,

(1754); Dublin to C-in-C, (1820),

4 August 1914, ibid.

[22] C-in-C to Admiralty, no. 398, 4 August 1914 and minute by Leveson,

initialed by Sturdee, PRO Adm 137/HS19.

[23] Ships’ Logs, HMS Indomitable,

HMS Indefatigable, 4 August 1914, PRO Adm 53/44830, 44809.

[24] C-in-C to General, (1941), 4 August, NSM,B; Lumby, p. 163. C-in-C to

Admiralty, no. 399, 4 August, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, p. 165; Ship’s Log, HMS Inflexible, 4/5 August 1914,

PRO Adm 53/44838.

[25] Milne to Admiralty, 20 August 1914, para. 20, Lumby, p. 216 [my

emphasis].

[26] Naval Staff Monograph, Vol. VIII (1923), The

Mediterranean 1914-1916, para. 21, PRO Adm 186/618.

[27] On 10 August Milne gave instructions that ‘Should Goeben

enter Suez Canal she must be blockaded and on no account allowed to pass

south.’ Milne to Mr Cheetham (Cairo), no. 77, 10 August 1914, PRO Adm

137/HS19. However the Foreign Office had a fit of scruples and Cheetham, the

Chargé d’Affaires in Kitchener’s absence, was informed later the same

day: ‘If Goeben enters the Canal

telegraph for instructions before allowing her to proceed through it, but I

doubt whether she can be stopped without a clear breach of the

Convention.’ Grey to Cheetham, no. 81, 10 August 1914, ibid.

The Convention of Constantinople of 29 October 1888, relative to the Suez

Canal, provided that belligerents could have free passage on condition that

they made no stay in the Canal, committed no warlike acts, and took in only

a minimum of coal. See, Bertie to Grey, no. 398, 12 October 1908, BD, V, no.

365, pp. 430-1.

[28] C-in-C, Medt to Admiralty, no. 401; Admiralty to C-in-C, Medt., no.

222, 5 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/HS19; Lumby, p. 165.

[29] C-in-C to General, (1941), 4 August 1914, NSM,B; Lumby, pp. 163-4.

[30] Ship’s Log, HMS Chatham,

5 August 1914, PRO Adm 53/37560.

[32] Midshipman’s Journal, B. B. Schofield, Wednesday, 5 August 1914,

IWM BBS2.

[33] Der Krieg Zur See, p. 41.

[34] Kopp, Two Lone Ships, p.

35.

[35] In December 1915 the Admiralty’s intelligence department

established the identity of some of the steamers involved: in addition to General, the German warships had, in all probability, coaled from SS Mudros of the German Levant Line

and SS Ambria of the Hamburg-Amerika

Line. Both these ships had then been laid up at Syracuse and were eventually

sequestrated by Italy when that country entered the war. Memorandum by

Aubrey Smith, Intelligence Department, 11 December 1915, PRO Adm 137/879.

[36] For details of this incident and its aftermath, see appendix ii.

[37] There is some confusion over the spelling of the Master’s name:

Keble Chatterton, a reliable authority, gives it as P. A. Eggers, however

the Log of the S S Wilster gives

Paul Eggert — see, PRO B[oard of] T[rade] 165/782.

[38] See, Identity of alleged

British collier from which Goeben coaled, PRO Adm 137/879; E Keble

Chatterton, Dardanelles Dilemma,

p. 25.

[39] Rodd to Foreign Office, no. 175, 5 August 1914, Lumby, p. 167.

[40] Rodd to Admiralty, rec’d 5.50 p.m., 5 August 1914, PRO Adm

137/HS19.

[41] Grey to Rodd, 6 August 1914, ibid.

[42] Der Krieg Zur See, p. 43.

[45] Admiralty Staff of the Navy to Goeben,

no. 61, no. 62, 5 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/4065.

[47] Constantinople to Foreign Office, no. 416, 3 August 1914, Kautsky, German Documents, no. 795, p. 562.

[48] Ibid., no. 426, 4 August 1914, Kautsky,

no. 852, p. 588.

[49] Admiralty Staff to Goeben,

no. 66, 7 August 1914, PRO Adm 137/4065; see also, Trumpener, Reassessment, p. 177, note 25.

[50] Der Krieg Zur See p. 46.

[51] Souchon, pp. 488-9; Trumpener, Reassessment,

p. 176.

[52] Halpern, Naval War in the Medt.,

p. 16.

[53] Souchon to Haus, 2.12 a.m., 5 August 1914, quoted in Der Krieg Zur See, p. 43.

[54] Halpern, Naval War in the Medt.,

pp. 17-18; Der Krieg Zur See, p.

44.

[55] Der Krieg Zur See, pp. 45-6.

|

|

Ships of the Victorian & Edwardian Navy :

I have been drawing the ships of the

Victorian and Edwardian Navy for twenty

years for my personal pleasure and I am

including some of these drawings on this

site in the hope that others may find them

of interest.

The original drawings are all in pencil.

Reducing the file size and therefore the

download time has resulted in some loss of

detail.

A set of postcards

featuring eight of my drawings is now

available for £2.50, which includes postage

anywhere in the world.

For more

information please click on the drawing

below:

|

|

The Links Page :

As the range of our activities

is so diverse, we have a number of different

websites. The site you are currently viewing is

wholly devoted to the first of the three

non-fiction books written by Geoffrey Miller,

and deals specifically with the escape of the

German ships

Goeben and Breslau to the

Dardanelles in August 1914. The main Flamborough

Manor site focuses primarily on accommodation

but has brief details of all our other

activities. To allow for more information to be

presented on these other activities, there are

other self-contained web-sites. All our

web-sites have a

LINKS

page in common, which allows for easy navigation

between the various sites. To find out where you

are, or to return to the main site, simply go to

the

LINKS

page.

|

|

|

|

HMS Berwick

[Original artwork © 2004 Geoffrey

Miller] |

|

Geoffrey Miller

can be contacted by:

-

Telephone

- 01262 850943 [International:

+44 1262 850943]

-

Postal address

-

The Manor House,

Flamborough,

Bridlington,

East Riding of Yorkshire, YO15 1PD

United Kingdom.

-

E-mail

-

gm@resurgambooks.co.uk

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|